I didn’t read about the Swastikas in Rudyard Kipling’s books as early as I might have. The reason is that Jean-François Nadeau’s book on Canadian and Quebec support for Nazism in the days of the Third Reich (Adrien Arcand, führer canadien; Lux Éditeur, 2010) is critically covered in Swastikas.

I tend to read on public transit, and displaying non-defaced Swastikas has always struck me as wrong. But you can’t vandalize a library book, least of all one you respect. So, too busy at the time to read it at home, I ended up returning the book mostly unread.

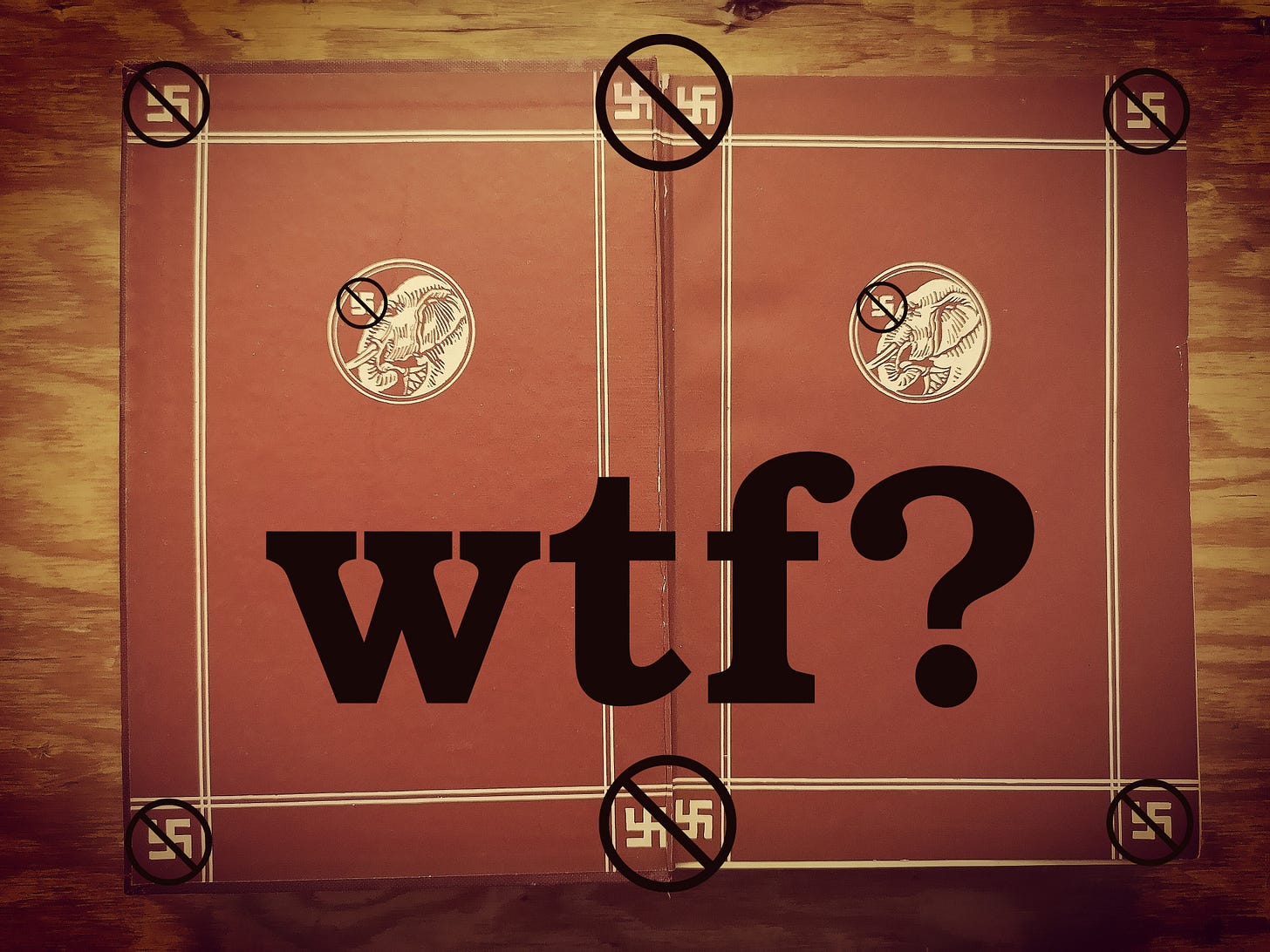

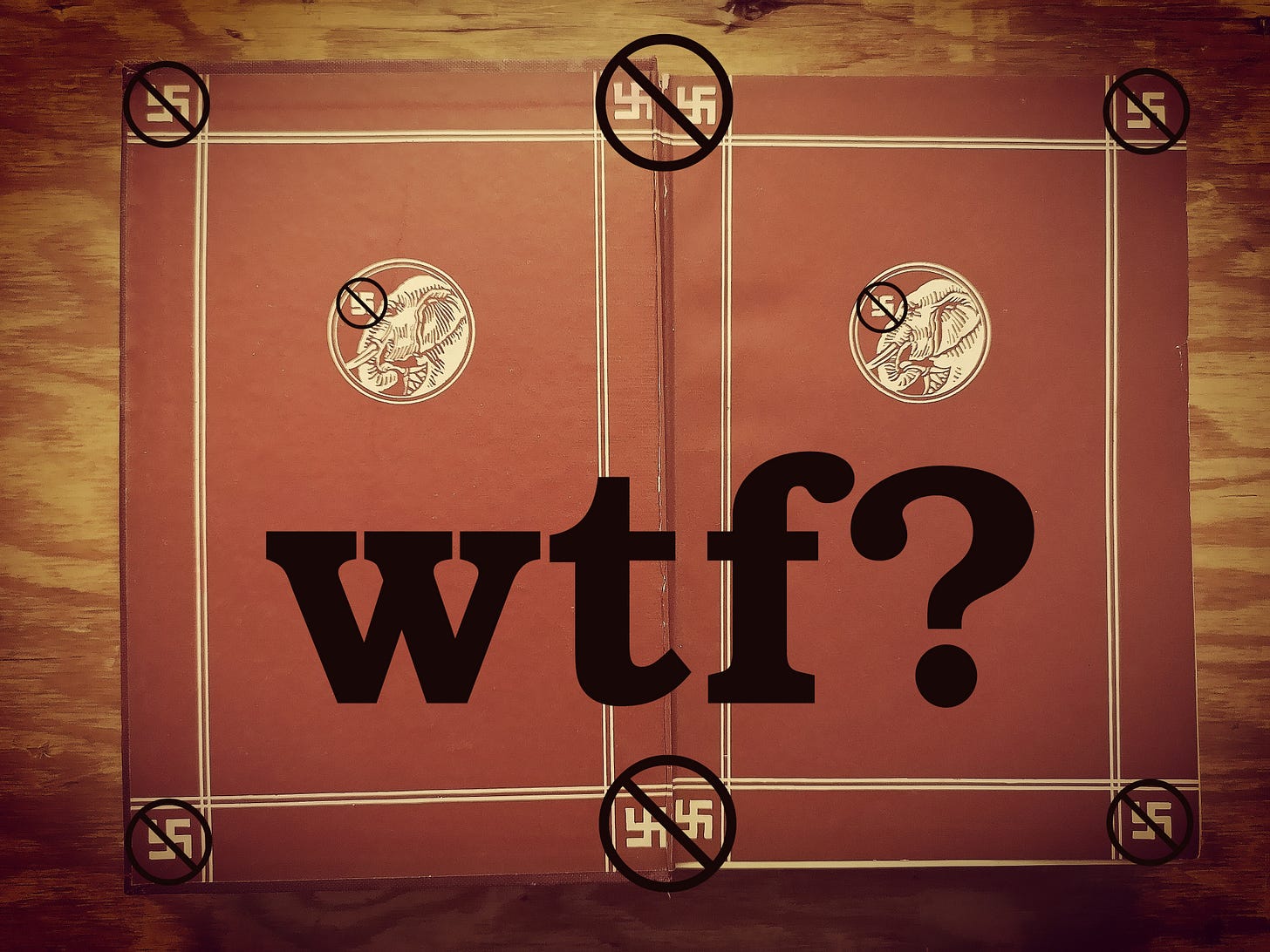

Had I read Nadeau’s book, I would have learned about Kipling’s fondness for Swastikas well before I ran across a used poetry collection of Kipling’s. Nadeau, to his credit, does record the Kipling–Swastika connection. As it was, I only learned about it when I happened upon the Kipling poetry collection in a used bookstore. I didn’t go searching for a jarring design, mind you. The book just happens to be covered in fully twenty-two Swastikas, including the ten featured above. Hence wtf.

I like Nadeau. And his book is valuable. But his line on Kipling’s Swastikas is super odd. The Swastikas on Kipling’s work, Nadeau writes (p. 208), should not obscure the fact that Kipling’s contribution to the British war effort during World War I included violent attacks on Germans. Nadeau records a quote from Kipling that you can also find in Harold Lasswell’s classical guide to propaganda: “there are only two divisions in the world to-day – human beings and Germans.”

The Kipling–Swastika connection deserves attention. But Kipling’s anti-German writings do little to explain it away, even if the pre-Nazi resonance of the Swastika can be debated. Nadeau has contributed to an important discussion about the heritage of white supremacy. But this oddity is a reminder that shedding our confusions about this heritage will take ongoing work.

About this post: a notepad in html

For reasons that I have tried to think through elsewhere, the current information environment is extremely confusing. Political contradiction is so pervasive that it might not bother too many people if Kipling were a straight-up Nazi, even if he were still honoured. We’re past things making sense.

After all, the GQ types kvell, weren’t the Nazis at least slick? That video is closing in on four million views. God damn.

Anyway, amid this mess, a friend sent me an interesting write-up on what Cory Doctorow calls the Mimex Method of open-notebook research. You can read it for yourself. The upshot from my end will be more casual posts like this one.

The tech-savvy quote a related idea from Linus Torvalds. For those of us more accustomed to pencil and paper, Doctorow calls for something similar: research collaboration and database openness. Basically, Doctorow proposes that people write out their notepads in html.

This post follows Doctorow’s advice. So here are some notes on the Kipling–Swastika connection and the history that lies behind it.

“Lest We Forget”: An icon of official racism

Earlier this century, the Senegalese political scientist Doudou Diène observed on behalf of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) that the problem of Canadian white supremacy is, in the first instance, a problem of design.

“The ideological mainstay in the build-up of racism and discriminatory practice throughout North America, from slavery to colonization, was the cultural contempt in which the dominated communities, whether native or African, were held,” reads the Diène Report (paragraph 79). “It is due to this long-term build-up that racism has come to imbue the culture, mentalities, behaviours and even the deepest subconscious layers of the peoples of the region.”

In Canada as throughout the former British Empire, Kipling is a leading icon of the era of official white supremacist acculturation. The pioneer of Canadian curriculum studies, George S. Tomkins, observed that curricular material from local imperial novelists “formed an admixture with the writings of Kipling and many others that dwelt on imperial glories, the whole forming the colonial curriculum to which several generations were subjected.”1 This story runs parallel to that of the residential schools.

The Diène Report implored us to develop an intellectual and educational strategy to deal with the white supremacist hatreds layered into Canadian society by this process, warning of the predictable: the explosion of white supremacist hate that has since been documented by Britain’s Institute for Strategic Dialogue, Barbara Perry, and the Canadian Anti-Hate Network.

Instead, today schools A Mari Usque Ad Mare display the phrase “Lest We Forget,” which was introduced into our political culture by Rudyard Kipling himself, the writer who also inspired the main publicist of the second Ku Klux Klan.

No wonder this screws with the mind. The about section of this substack links to a number of classical guides to empire’s psychological warfare, i.e., the crafting and sublimation of white supremacist myths. One of those guides is Gustave Le Bon’s Lois psychologiques de l'évolution des peuples, linked in its English translation.

Le Bon’s book is a signal example of the racist heritage that, alas, lies just under the surface of Quebec and Canadian politics. Should an international visitor fly into Montreal and get into the city by public transit, they will first encounter the métro at Lionel-Groulx. Groulx’s novel L’Appel de la race famously quotes Le Bon’s Lois psychologiques, including references with page numbers. For context, see Léandre Bergeron’s Petit manuel d’histoire du Québec.

Should an international visitor fly into Toronto, meanwhile, they will first reach the subway station at Kipling. I vividly recall a more detailed reference to Kipling encountering Le Bon during his youth in India. For the moment, I will just note that Kipling repeatedly met Le Bon and published “a brief note in the Civil and Military Gazette, 6 February 1883, on the appearance of Le Bon’s La Civilisation des Arabes with a reference to Le Bon’s Indian visit.”2

The details of their encounters aside, Le Bon missed no occasion to praise the psychological warfare waged against Indians by the British Empire’s Indian Civil Service (ICS). Le Bon wrote that the bullsh*t artistry that is racial deception found its finest expression in the way “sixty thousand English are able to maintain beneath their yoke two hundred and fifty millions of Hindoos,” and he celebrated ICS operatives as “the masters of the most gigantic colonial empire known to history.”

Kipling was essentially a mouthpiece for ICS politics. He was also the representative of the racializing school system that most impressed Le Bon. “‘I try to pour iron into the souls of my pupils,’ said an English schoolmaster to Guizot, when he was visiting the schools of Great Britain.” Le Bon saw this as the only way to forge the racialized core of a conquering imperial system.

In Canada, the iron that blocked critical debate concerning the residential school system is finally showing signs of wear. So what is most bizarre about the continued “Lest We Forget” phraseology is that Kipling has been officially flagged as a problem in Canadian education ever since official racism was overturned in the 1960s. He is the acknowledged representative of the age when Canadian schools were Teaching Prejudice as a matter of policy, to borrow the title of a report commissioned by the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

“The spirit of empire marches bravely through the pages of many textbooks,” the authors found, citing Kipling’s presence in the curriculum (p. 94). And the spirit of empire, they restated for the record (p. 33), lies: “Our investigation of the social studies texts authorized for use in Ontario Schools in 1968 indicates that the words which are used to describe minority groups [sic] seem almost guaranteed to build up stereotypes that discredit the authors and, in effect, defraud the readers.”

Defraud is the word for it. The poem that introduced “Lest We Forget” into official empire celebrations played on the Christian background of its audiences with the fraudulent cynicism that was Kipling’s stock in trade. “Throughout Great Britain and the colonies,” wrote one reviewer, the poem produced “a thrill of contrite and reverent patriotism such as the English have seldom felt, and such as no other nation, except if it be our own, is at all still capable. No one of Anglo-Saxon race . . . can read it unmoved.” In fact, Kipling had few beliefs beyond the will to power.

He later expressed his contempt for Christianity, even as students were told to treat his poem as a pious hymn. “I’m no Christian – Allah knows,” Kipling wrote to H. Rider Hagard, joking at the expense of his loyal readers, as well as at the expense of the Indian Muslims against whom ICS racism was principally directed.3

With irreligious cynicism, Kipling anticipated Kevin Spacey’s character in The Usual Suspects, looking around for whatever themes, Christian or Nietzschean, would serve the purposes of his work. Like Nietzsche, Kipling looked to antiquity, Roman as well as Greek. “No doubt the fact that Mithraism,” for example, “was essentially a military religion and was widespread through the armies of the Empire goes some way to explain the attraction it held for Kipling.”

Designed with Swastikas, his books were then peppered with racial epithets. Here is Kipling again, the British Empire’s prized wordsmith: “Negro applied to an individual is, in our mind, midway to ‘coloured gentlemen,’” Kipling explained to one contact; “I wanted the lowest and clearest contrast. Hence ‘n****r’.”4 I apologize for quoting this filth. But just how, again, are schools still paying homage to this author? How hate crimes follow is easier to understand – if not to tolerate.

Now, I hope it can be trusted that this is not a personal grudge. But Kipling was keen to complain that were it not for “the Micks and the Yids,” WWI propaganda in North America would have made for a smoother experience.5 What he meant should concern everyone, including those he mocked as credulous “Anglo-Saxons.”

Toward the end of this post, I will get to the question that most directly concerns social scientific credibility. But let’s think on the Swastikas first.

Why Kipling thought Einstein was sent from hell

Much of our society so distorts what antisemitism is really about (hint: not Palestinian freedom struggles) that I will take this occasion to restate some classical basics. Lest we forget, Kipling’s rants about “the Yids” speak to the real problem of racism in local heritage, a problem that anti-Palestinian smears only compound.

“Do you notice,” Kipling wrote a friend in the autumn of 1919, “how their insane psychology attempts to infect the universe?”6 Einstein was the immediate instrument of the supposed psycho-racial infection that concerned Kipling. But to ask who “they” were – Jews, Germans? – is to wade knee-deep into racial bullsh*t.

So let’s wade. John Buchan was to Scotland what Kipling was to England. And he showed how the “they” could from a British imperial perspective be both German (keywords Teutonic, Hun, Boche) and Jewish (Kipling’s “Yid”). “Take any big Teutonic business concern,” Buchan had one of his characters say. At the top of the Teutonic top, so this story goes, “ten to one you are brought up against a little white-faced Jew in a bath-chair with an eye like a rattlesnake.”

I have written about this elsewhere. It is all out in the open. But as Mordecai Richler observed, we are expected to accept Buchan’s vicious colonial racism and antisemitism since, “like many another promising young anti-Semite, Buchan mellowed into an active supporter of Zionism, perhaps in the forelorn hope that hooky-nosed gourmets would quite Mayfair for the Negev.”7 In order to serve as Governor General of Canada, Buchan was raised to the British peerage as Lord Tweedsmuir, and he is still publicly honoured as such.

This brings us back to Kipling’s anti-German propaganda during World War I. In order to falsify allegations of antisemitism for anti-Palestinian use, it has been necessary to gut understanding of how antisemitism really developed as a modern political program. But the image of Germany cuts in all sorts of directions.

A turning point in antisemitic history was the Dreyfus Affair, a famous expression of the later British wartime theme: that Jews were more loyal to Germany than to their home country (France, or Britain, or whatever). In Germany, the racist right picked up on the old British allegation that the French Revolution was the work of “Old Jewry,” in Edmund Burke’s classical fantasy. The point for these liars was to forge racialized unity with whatever version of the myth fitted local circumstances.

What might seem weird about this program is the tension within its focus on alleged Jewish radicalism. You can see the basic focus in Buchan’s insistence that the noble Russian Czar was a victim of communistic Jewish perfidy. You can also see it in Kipling’s insistence that organized job action by British workers was, if empire and racial truth are to be believed, the work of “the Hun, the Bolshevik and the Jew of Poland chiefly.”8 In Germany, a parallel story held that Jews and France were the twin spearheads of an African onslaught on German whiteness.

The British version of this story was the basis for Kipling’s attack on “the Micks and the Yids” of the United States (ethnically my folks at the time, in full disclosure). Irish activists had a way of reminding U.S. audiences that the British storytellers who talked freedom also boasted some of the world’s worst stormtroopers, whose fanboys to this day sing about the massacres that brought them “up to [their] knees in Fenian blood.” Meanwhile, Jewish leftists held their own. Before the British delivered Palestine to the Shtadlan, even parts of the Zionist movement had the good sense to denounce what the Yiddisher Kemfer called “Wall Street’s war.”9

But in the British Empire, antisemitism was never the principal form of organized race-hate. The official culture of British racism was focused above all on ruling India. As far as it goes, Jews were classed by traditional European racists as “Asiatics,” and British Empire publicists spun Asiatic fantasy webs into which the Jewish bogeyman was occasionally drawn. “Who could doubt, for instance, that the assassination in 1909 of an eminent member of the Indian Civil Service, though carried out in London by an Indian, had really been engineered from Paris by a German woman and a handsome Jewess who, owing to the combined support of Jewry and of Continental Freemasonry, wielded immense power?”10 But notice that even this story alleges nefarious German–Jewish links.

In its heyday, antisemitism as English anti-radicalism was spelled out in its standard details by Winston Churchill. Crucially, the idea that Jewish people are just another group of people, with the regular range of human tendencies, has no place in the folklore of Western Christendom. From Burke on, the Christian theological fixation on Jews has given way to modern stories of the most bizarre kinds, including the latest anti-left & anti-Palestinian Crusades by those who in earlier times would have been telling the old stories about “Judeo-Bolshevists.”

So a century before leftists in Britain were attacked from the right for opposing empire’s assault on Palestine, Churchill was accusing their predecessors of being dupes of communistic Jewry. Lenin, so Churchill alleged, was a German agent sent to disrupt law and order in Russia, and so an instrument of “the most formidable sect in the world” – see Burke, see Buchan – who infected Russia “the same way that you might send a phial containing a culture of typhoid or of cholera to be poured into the water supply of a great city.” English socialists, Churchill declared, where just dupes who “believe in the international Soviet of Russian and Polish Jews.”11

The theme of the “international Jew” was never as important to the work of English storytellers as it became in Germany. But you can refer here (all Churchill quotes from that source in print) for Churchill’s fullest explanation of his own antisemitism. For Churchill, “the Jew” was angel and devil, since “this mystic and mysterious race had been chosen for the supreme manifestations, both of the divine and the diabolical.” In Churchill’s story, the international devil-Jew could yet be redeemed.

Under the heading “International Jews,” Churchill restated Burke’s “Old Jewry” tale with an anti-communist twist, the Russian Revolution standing in for the French. Enter what Churchill calls a “sinister confederacy” for the poor over the rich: your Karl Marxs, your Rosa Luxemburgs, your Emma Goldmans, to cite three whom Churchill names. All who march under the banner of “impossible equality” stood, so the story suggested, with this diabolical sect, horns and red flags entangled.

In time-worn British style, Churchill proposed a response of carrots and sticks. The stick would strike the “International Jew” and all fellow-travellers; the carrot would be Palestinian land and tales of Jewish redemption. Some of those whom Churchill called “National Jews,” i.e. Westernized patriots, would be encouraged to wield a stick handed to them for this purpose, while cheering the establishment by other “National Jews” (Churchill’s vision for Ostjuden) of “a Jewish national centre in Palestine” as “the temple of Jewish glory.” The result would symbolize the triumph of empire and the defeat of the left – the proof of power that leftists’ “sinister confederacy” would be “repudiated vehemently by the great mass of the Jewish race.”

We once more see the standard theme flagged by Mordecai Richler.

In Germany, the story took a different form, reflecting the relative prominence there of anti-Jewish racism as an instrument of race-power cohesion. Between the world wars, this took on unprecedented proportions. The Nazis, and Hitler in particular, packed a multi-issue racism tightly around this theme. To conflate Hitlerian politics with the varied attacks on “Judeo-Bolshevism” documented by Paul Hanebrink would be a mistake. Shared themes do not flatten differences.

Across boundaries, however, what made antisemitism work as an anti-left program was partly its hostile torquing of left critiques of management and high finance. To the extent that Jews could be represented, à la Buchan and Protocols of the Elders of Zion, as a two-pronged threat encompassing capital and communism alike, the call for racial cohesion across classes could resonate. It is infinite perfidy, so the story went, the Jewish international was creating a boom-bust cycle that threw workers of good stock onto the streets, where they fell prey to the seductive arguments of leftist organizers (all of whom could be cast as “Jewish,” irrespective of ethnicity).12 That is how race-power hate was sold in Germany as worker defense, with the aim, and partial effect, of undercutting the class basis for anti-fascist resistance.

So which white supremacists used the Swastika first, where, and why?

The details get weird, fast. The Swastika’s migration from old Norse and Indian iconography through the Euro-supremacist Aryanism of occult weirdos reaches Kipling and the German far right in ways that are too bizarre to productively detail. All I want to underline here is that it was typical for British imperial antisemites to write against Germany. According to their racial anti-radicalism, “the Bolsheviks were said to comprise chiefly Jews and Germans, who, being active and enterprising, were able to tyrannize the dreamy Russians,” etc., etc.13

It was against this backdrop that Kipling saw Albert Einstein emerge from hell.

Albert Einstein’s horns

In 1964, Malcolm X memorably joked at the Oxford Union about his “horns.” Kipling, for his part, nearly saw a pair grow from Albert Einstein’s head.

The themes chime with some keynotes of German antisemitism, but for the sake of space, I will mostly conclude with English details. In a poem from Songs from Books to which I will return in future posts, Kipling proposes that racial myths require coded inside meanings for the imagined-as-organic racial community alone.

He writes: “The Stranger within my gate, / He may be true or kind, / But he does not talk my talk – / I cannot feel his mind.” Racial inside meanings, Kipling proceeds to explain, are by definition only useful if restricted to imagined racial kin. “The men of my own stock / They may do ill or well, / But they tell the lies I am wonted to, / They are used to the lies I tell.” Always and forever, the fiercest British racism expressed itself in the language of horticulture. This was no exception: “This was my father’s belief / And this is also mine: / Let the corn be all one sheaf – And the grapes be all one vine, / Ere our children’s teeth are set on edge / By bitter bread and wine.”

In defense of elegant European fables that could be sold as scientific truths, early interwar Nazi agitation in Germany made hatred of Einstein a white-power cause célèbre. This hatred in turn became an official theme under the Third Reich, as “scientists backed by the regime, among them two Nobel prize-winners, reproached Einstein and his German imitators (to repeat C. G. Jung’s expression) for having developed the model of an arbitrary and artificial universe, against which they set the natural and tri-dimensional universe of ‘German physics.’”14

More work is needed on this subject, which bridges the record of organic racial (lies as) truths and classical debates about surface phenomena and critical scientific inquiry. Anyway, Kipling nodded at the early attacks on Einstein.

Oddly, although he singles out Einstein as “a Hebrew,” I now notice that it is not impossible that Kipling is describing Einstein, “nominally a Swiss, certainly a Hebrew,” as a German as well as a Jewish devil. Kipling restates the association, attacking coverage of the theory of relativity in “the Jew and pro-Boche papers.” The wording leave some ambiguity concerning whether “the Jew” or “the Boche” is in this case from hell. But this is Kipling’s core message: “When you come to reflect on a race that made the world Hell, you see how just and right it is that they should decide that space is warped, and should make their own souls the measure of all Infinity.”15

Quite apart from the German arguments then unfolding in parallel (and on this subject, much more dangerously), a British parliamentary debate around the same time provides another clue concerning the English racial subtext.

The debate concerns Britain’s Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919. At the time, there was a Jewish member of British cabinet, Edwin Montagu. Now, a person does not get appointed Secretary of State for India for being faint of heart; the point is not to romanticize Montagu. His entire record, indeed, is beside the point.

The point here does not even concern the Jallianwala Bagh massacre as such. Yes, a British commander showed the world what the ICS normally hid when he proudly fired 1,650 live rounds of ammunition at Indian demonstrators for the crime of demonstrating in their own country without British permission. And yes, Montagu denounced this massacre as morally as well as strategically abhorrent. My point in this note concerns how English racialists responded.

“Montagu got excited when making his speech,” wrote the chief whip, “and became more racial and Yiddish in screaming tone and gesture, and a strong anti-Jewish sentiment was shown among the normally placid Tories of the back bench category.”’16 Notice the presumption that English racialism is not racial at all, on the implicit grounds that the Englishman is the universal man and all else is deviation. Notice too this next line on “induction.” According to the Times, Montagu had failed to defer to “our inductive English method of political argumentation.” At issue for the Times was not place of birth, language, or citizenship, but race: “Mr. Montagu, patriotic and sincere English Liberal as he is, is also a Jew, and his excitement had the mental idiom of the East.”17

So what is this “induction” that taught advocates for empire not to speak of their viciousness, and to claim racial superiority – which is to say virtue – in quieter code? For his part, Kipling insisted that whatever it was, it was the cultivated product of a “training that from cot to castle runs – / The pitfall of the stranger but the bulwark of thy son.” As Le Bon, Benjamin Kidd, and other experts explained, this tradition was structured around a race-power mythology whose outward language was a front.

It is comforting to think that we are past all of that. On the other hand, it would help if students who follow up on Remembrance Day slogans didn’t find themselves face to face with a writer like Kipling, assaulting them with racial epithets.

I’ll leave it at that for now. But do you see this book?? Really: wtf.

George S. Tomkins, “National Consciousness, the Curriculum and Canadian Studies,” Journal of Educational Thought 7, no. 1 (1973), 12.

Thomas Pinney, ed., Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vol. 4 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1990), 577.

Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vol. 4, 219.

Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vol. 3, 159.

Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vol. 4, 555.

Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vol. 4, 592.

Mordecai Richler, Shovelling Trouble (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1972), 62.

Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vol. 4, 72.

Quoted in Melvin I. Urofsky, American Zionism from Herzl to the Holocaust (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1975), 201.

Norman Cohn, Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1969), 154.

Harry Defries, Conservative Party Attitudes to Jews, 1900–1950 (London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2001), 81–82.

See Cohn, Warrant for Genocide, 114.

Cohn, Warrant for Genocide, 150.

Léon Poliakov, The Aryan Myth: A History of Racist and Nationalist Ideas in Europe, translated by Edmund Howard (London: Chatto Heinemann, 1974), 315.

Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vol. 2, 592.

As quoted in Meghnad Desai, The Rediscovery of India (London: Allen Lane, 2009), 138.

As quoted in Derek Sayer, “British Reaction to the Amritsar Massacre, 1919-1920,” Past & Present 131 (1991), 157.